Buoyed by the success of his first full length animated film, Snow White, Walt Disney decided to plunge ahead with more animated films, despite (justified) concerns about their expense and continued profitability. Far from worrying about tiny issues like budgets—at least at this point—the new movies, he decided, would not merely follow Snow White’s success and innovative filming techniques, but be even more innovative and lavishly detailed. Starting with Pinocchio.

The story itself proved remarkably difficult to bring to screen, requiring three years of development and work. The issue was threefold. First, the animators had to create a story from a book that, as I noted last week, redefined the idea of “episodic” and “plot driven,” with far, far too much story for a series of films, let alone just one film. Second, as I also noted, Pinocchio the book has a distinct lack of likeable characters. It’s certainly easy enough for children to identify with Pinocchio and his desire to just run off and have fun instead of going to school or working, but “easy to identify with” is not quite the same as “likeable” or “easy to cheer for,” and the film needed to bridge that gap. And third, they had to not just animate a puppet, but attempt new things in animation, a challenge that daunted animators still recovering from Snow White.

Recognizing just from the storyboards and initial animation that this was not going well, Disney halted the project for six months until those issues could be solved—setting some of his animators on another project, an expansion of the highly successful Silly Symphonies, which eventually became Fantasia.

And which eventually led to the inevitable—“Is that one of the goldfish from Fantasia” from viewers watching Pinocchio, or, alternatively, “Why is the goldfish from Pinocchio dancing in this film?” from viewers watching Fantasia. It’s not quite the same goldfish, but the look and animation techniques are the same, as are many of the movements. The two films were developed and animated separately, but animators did move back and forth between the two projects, allowing Fantasia to be released just ten months after Pinocchio.

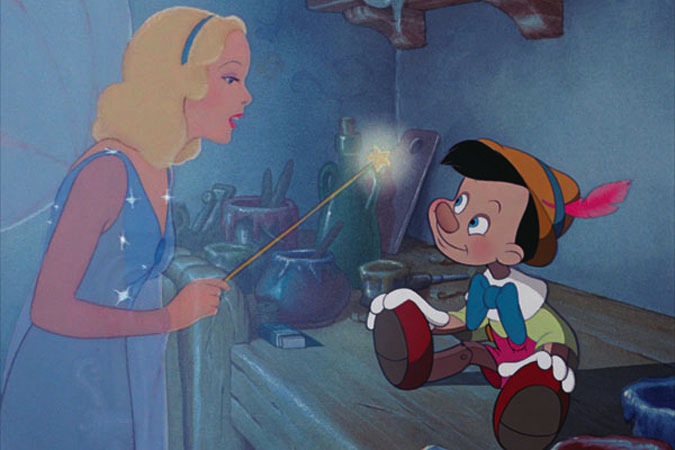

Eventually, the Disney animators managed to deeply compress the book, mostly paying attention only to the (somewhat) kinder second half, and transform Pinocchio into a rounder, cuter, and kinder figure. (Notably, movie Pinocchio does not run around hitting people. This is a Pinocchio I can cheer for.) And, in what was to become a classic Disney technique, Disney transformed several characters and added a few more: Geppetto gained an adorable kitten called Figaro and a delightful goldfish called Clio; the dead Cricket became a living Cricket with a more cheerful, less priggish personality—and one capable of making mistakes; and the Blue Fairy stayed, well, a Blue Fairy, which did wonders for her personality and plotline.

Sidenote: For the voice of Jiminy Cricket, Disney hired ukulele player and singer Cliff Edwards, partly because of Edwards’ relationship with RKO Radio, Pinocchio’s initial distributors. In a serious attempt to gain recognition for the ukulele, Edwards made at least 600 recordings over the course of his life (many have been lost), to find himself remembered only for “When You Wish Upon a Star,” which has no ukulele playing whatsoever. Legend claims that he spent his later years wandering around the Disney studios drunk or high or both, hoping for voice work; sympathetic Disney animators gave him lunch instead.

Second sidenote: Jiminy Cricket and Figaro ended up becoming popular enough to star in other Disney productions—something few characters in the early Disney films managed—but although this is bad of me, I must admit that I much prefer the grungy and generally voiceless Gideon the cat, Honest John’s sidekick, who handles problems by hitting them over the head, and has certain—how can I put this—questionable food choices. He’s absolutely disgusting, and there’s no reason for me to love him. And yet.

Though I also like little Figaro the kitten, who has a little bed of his own but, after a questionable request from Geppetto to open a window (Geppetto! Kittens need their sleep!) happily crawls right into bed next to Geppetto where every cat belongs. And sticks right by Geppetto for the rest of the film, right down to fishing by the old man’s side. Everyone, AWWWWWW. And with that out of the way, back to the post.

With character and storytelling problems somewhat cleared up (though, true to form, Walt Disney demanded continuous changes to both story and characters throughout production, a habit that was to drive his chief animators bonkers for decades), the animators pushed on to the work of creating the film. Three sequences in particular pushed the art of animation at the time: an early sequence near the opening, where animators worked to show the story from the perspective of a jumping cricket, making the entire image bounce up and down, while continuing to animate objects within the image and create the illusion of depth through multiple images; an almost dreamlike underwater sequence that forced animators and special effects artists to give Pinocchio and Jiminy a shimmering, underwater look; and nightmarishly difficult to animate sequence with a moving Pinocchio in a dangling cage in a moving caravan—this last one particularly tricky since the backgrounds and the animated cel all had to move, and all had to move naturally, in sequence.

Other astonishing (and expensive) sequences included an early scene with multiple cuckoo clocks—each involving separate animated figures, which had to be carefully coordinated, and a later scene at Pleasure Island (something that decades later Disney would cheerfully adapt into an additional entertainment area at Walt Disney World).

The difficulty of all this—added to the initial delays, Walt Disney’s ongoing demands that his animators redo already animated sequences, and the pressure of simultaneously producing Fantasia, especially in the last few months of the film—may help explain why so much of the first 26 minutes of Pinocchio is focused on the difficulties of getting a good night’s sleep—or, for that matter, getting any sleep at all in a world filled with ongoing sound and clocks and annoyances.

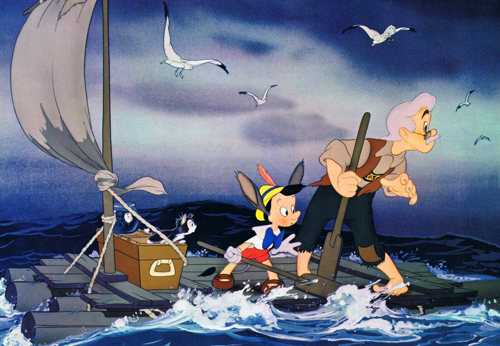

But that theme is soon abandoned for the dominant themes of the film, temptation and heroism, as Pinocchio finds himself continually tempted away from the correct path of attending school on a regular basis; Jiminy Cricket finds himself constantly tempted to just give up; Figaro the kitten is constantly tempted to just laze in bed and not do all of those annoying things like opening windows for the guy who feeds him (to be fair, I kinda feel that Geppetto is probably just as capable of opening windows as a small kitten is) and to be cruel to the goldfish (their developing relationship is a lovely subplot in the film); and even the bad guys find themselves tempted by easy money. And as Pinocchio (and to a lesser extent Figaro the kitten) goes beyond just trying to be good into real heroism—saving his father, the goldfish, Jiminy Cricket, and the kitten.

These are, of course, not particularly new themes, and Collodi’s book had certainly dealt with the temptation aspect, if more violently. But the idea of young, innocent boys leaving fun behind to sacrifice themselves for their elders was also very much on the minds of the many people in the late 1930s who had survived World War I—Walt Disney and his animators among them.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that, after lingering scenes of temptation and a striking scene of (mostly violent), self-centered young boys turning into donkeys, so much of Pinocchio focuses on the sequence where Pinocchio unhesitatingly saves his father. This is far longer than the equivalent scene in the book. And while some of that change might be thanks to the animators’ desire to show off the techniques they developed for underwater animated scenes, and some undoubtedly thanks to the need to have Pinocchio earn his transformation in a more exciting manner (in the book, he gets a job, which if decidedly more ethical than anything he did in the book before that, is not really exciting from an animated movie point of view), much of it seems to emphasize the theme that real boys—and men—are willing to make such sacrifices. It’s a bit too much to call Pinocchio a pro war film—that would be a theme Disney would take up later, after the outbreak of actual war—but it is certainly a film thinking about heroism.

Nor do I think it’s a coincidence that the scariest character in the film—so terrifying that he scares two of the villains—is an ordinary man who is collecting young boys to transform them into something else.

And this might help explain why Pinocchio, in contrast to its predecessor, is such a male dominated film—only two characters are female, and only one of those, the Blue Fairy, has a speaking role. It’s not exactly a question of simply overlooking women: Disney’s next two major films, Fantasia and Dumbo, would both heavily feature women—even if we can certainly question at least one scene in Fantasia and even if most of the women in Dumbo are pretty mean to a cute little baby elephant. It is partly a question of adapting the source material—most of the characters Pinocchio encounters in the book are male—but also a reflection, I think, of a perceived gendered response to war, which by 1939, as the animators furiously drew drawing after drawing in peaceful California, was clearly looming on the horizon.

Pinocchio echoes the late 1930s in another way as well: the near constant smoking. Almost everyone aside from Jiminy Cricket, Figaro the cat, and the Blue Fairy ends up heavily smoking at least once—although to be fair, for Clio the goldfish it’s more secondhand smoke, and for Monstro the whale, it’s regular, not tobacco smoke. Everyone else, though—Geppetto, Honest John, his skeezy cat companion Gideon, Stromboli, the Coachman, Lampwick, and even Pinocchio smokes, and smokes, and smokes.

Smoking, of course, was common in films of the 1930s and 1940s, with nearly every heroic figure lighting up at least once. Films used images of smoking to establish sophistication, flirtation, and sexuality. Interestingly, Pinocchio avoids this. Partly, of course, because none of the characters in Pinocchio are especially sophisticated—well, the fox does claim to have had a recent social encounter with a duchess, and the Blue Fairy is wearing something that would not be out of place in many fine 1920s dance clubs, but for the most part, Pinocchio is about characters on the margins of society. The closest anyone gets to sophistication is a puppet show filled with pratfalls: Pleasure Island is specifically aimed at an unsophisticated audience of generally rough boys.

But mostly because, for all the fun Pinocchio has with sight gags involving cigarette smoke (including a rather horrible scene where the grungy cat grabs a smoke ring from the air, dunks it into beer, and eats it), and for all of the smoking in the film, Pinocchio does take a rather uneasy stand towards smoking. Yes, Geppetto has a pipe, but he doesn’t use it that often: the chain smoking characters are all evil. And Pinocchio’s one attempt at smoking leaves him ill and helps give him donkey ears. Smoking may be common practice, the film notes, but that doesn’t make it a harmless one.

And speaking of practices less common in today’s films, a quick word of warning for those who haven’t seen the film: Pinocchio uses some common stereotypes about Italians, and one use of the word “gypsy” to mean “a liar and a cheater.” The word, however, is used in that sense by a villainous characters, and I think is meant less as a derogatory ethnic term and more as a further suggestion that the Fox and his Cat are not be trusted.

Smoking and the one ethnic slur aside, Pinocchio is a beautifully crafted piece of work, a film that should have made tons of money for its creator. Alas, Pinocchio was released at almost the worst possible time for Disney and RKO Radio, its distributor: 1940, when the outbreak of war in Europe prevented Disney and RKO Radio from distributing the film. Disney took an initial $1 million loss on the film—about 40% of its cost. Thanks to this, Disney was never to attempt animation on this level again until Beauty and the Beast and the later Pixar films.

Housekeeping note: We’re about to skip three films in the Disney lineup. Fantasia (1940) contains only two sequences based on a literary source, and in one case (The Nutcracker Suite sequence), only by really stretching the term “based on a literary source”—Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky may have written the score for a libretto based on E.T.A. Hoffman’s The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, but to say that Fantasia has absolutely no interest in that libretto or the story is to greatly understate matters. Disney did turn to Goethe’s poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” (English translation here) for inspiration for the central cartoon short featuring Mickey Mouse, but there the literary inspiration ends. Also, full disclosure: the dinosaur sequence always puts me to sleep.

The Reluctant Dragon (1941) was something quickly thrown together by Disney in a desperate attempt to recoup the unexpected losses from Pinocchio and Fantasia thanks to the loss of foreign markets for both films. It contains three cartoon shorts—Baby Weems, How to Ride a Horse, and The Reluctant Dragon, somewhat loosely tied together by the story of a man attempting to get Disney to make a cartoon of The Reluctant Dragon like HA HA can we all laugh now. (No.) The film turned out to be important in Disney history largely for How to Ride a Horse, the first of the “How to” Goofy shorts, and to a lesser extent for the footage of Disney animators, but otherwise, it’s pretty forgettable—including the one bit based on a literary source, The Reluctant Dragon, based on Kenneth Grahame’s story.

I hesitated over Dumbo (1941). Very technically, Dumbo is based on a literary source—if, that is, we again stretch the definition of “literary source”—a 36 page book with only 24 pages of very brief text. It was not, in fact, intended as much of a literary work: its creator Helen Aberson wrote it largely to demonstrate the possibilities of a new technology/toy, “Roll A Book,” where little readers would slowly turn a wheel to see illustrations and texts roll by. If you are wondering why you have never heard of this before, it’s because like so many great ideas, it went nowhere. Disney didn’t go for the technology either, but liked the story enough to purchase the rights to it—and keep the original text out of print. That it in turn has made it difficult to track down the full original text, so doing a Read-Watch of it just didn’t work out.

Which means that next up is Bambi: A Life in the Woods.

Brace yourselves.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.